Two months ago, I saw them on Marktplaats, basically the Dutch equivalent of eBay. There was no fixed price; instead, it was bid-only. Unlike most people who see bidding as a sport, I hate it. Too much, you’re a fool, and too little, you’re naive and insulting the seller.

I also hesitated because your choice of plants was a bit over-the-top floral. Don’t get me wrong; we share many of the same plants, such as the peonies and fuchsias. But my mostly shadow garden prohibits your abundance of lush pinks.

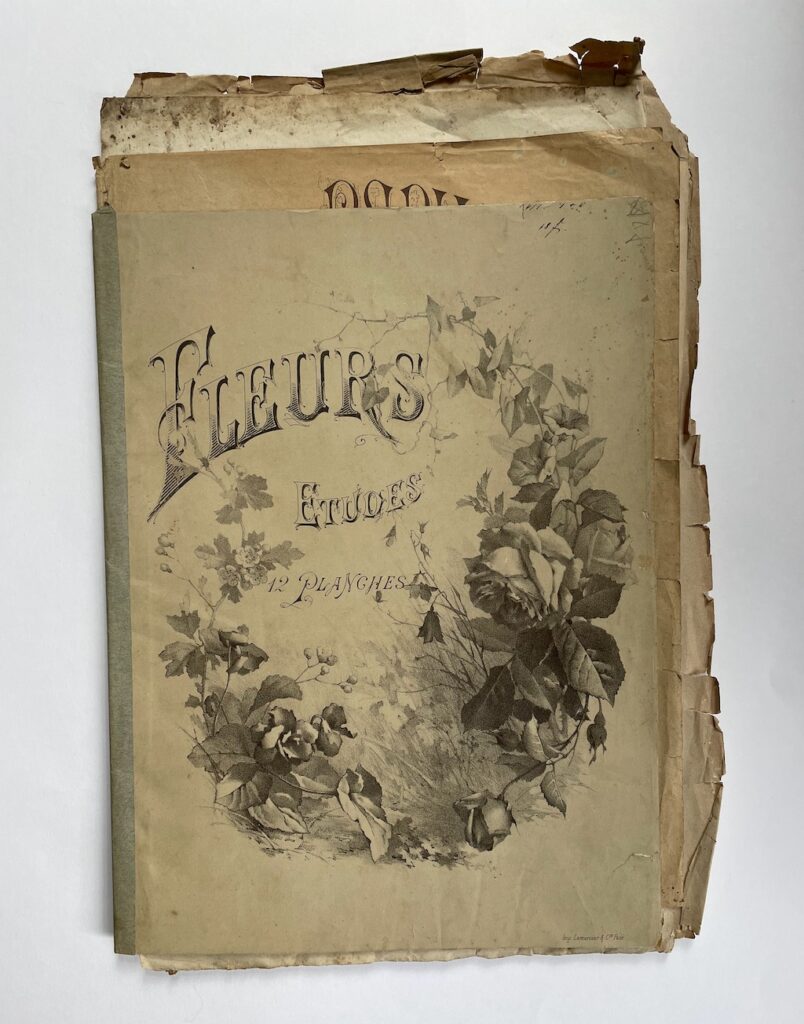

Despite all of these reservations, I kept returning to the ad. I would flick through the jpegs, zooming in on the details and checking if anyone made an offer. Mustering up enough courage, I finally placed a bid. The seller wrote back saying, “two hundred euros and they are yours.” A total of twenty-four added up to a little over eight euros a drawing, which seemed all in all pretty reasonable.

It reminds me of John Berger’s essay “How to Resist a State of Forgetfulness.” He also includes an illustration of a rose, but unlike yours, its lines are thick, clunky and simplified. He was over eighty when he drew it, and his outlines show the determined but unsteadiness of his hand. In both the essay and its accompanying drawings, he’s thinking through plants as a form of text. He writes:

During the last week I’ve been drawing, mostly flowers, motivated by a curiosity which has little to do with either botany or aesthetics. I have been asking myself whether natural forms – a tree, a cloud, a river, a stone, a flower – can be looked at and perceived as messages. Messages – it goes without saying – which can never be verbalized, and are not particularly addressed to us. Is it possible to ‘read’ natural appearances as texts?*

Berger’s use of the words “read” and “texts” is intriguing. What does it mean to study a flower like a book? Did he choose such phrasing because it felt near to him, within his linguistic register? What do these words bring to his understanding of the rose he drew? Unless reading an Exit sign in a burning building, reading is usually an intimate encounter and something done with concentration. It is an act of devotion, that which is given to an(other).

You chose to draw, but for me to pick up a pencil or paintbrush feels out of sync with the present and disconnected from who I am. As a child reared on an unhealthy amount of television and as someone with a short attention span, I struggled throughout art school with drawing and the patience the classes required. Compensating for my deficiencies, I learned to make energetic and gestural drawings which were more reflective of the drawer than the various posed models. Honestly, it was all a ruse.

Drawing realistically and remaining faithful to one’s subject seems impossible, but drawing realistically or otherwise to be faithful to drawing itself is something else. Whether it’s the technology of the brush, the pencil, the camera, writing etc., our connection to any subject of observation is imperfect and partial. Or, as Donna Haraway writes:

“The “eyes” made available in modern technological sciences shatter any idea of passive vision; these prosthetic devices show us that all eyes, including our own organic ones, are active perceptual systems, building on translations and specific ways of seeing, that is, ways of life. There is no unmediated photograph or passive camera obscura in scientific accounts of bodies and machines; there are only highly specific visual possibilities, each with a wonderfully detailed, active, partial way of organizing worlds.”

*Haraway, Donna. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1988, p. 575., https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

Looking at your dancing leaves, did you think about the novelty of photography and wonder whether your craft was nearing obsolescence? Did Darwin’s theory of evolution influence the way you saw the roses and the bees that pollinated them?

Maybe it wasn’t just the present but also the past that shaped your drawings. Perhaps you carried Carl Linnaeus, Maria Sibylla Merian, or Lise Cloquet with you too. I have a soft spot for Lise Cloquet. Her botanical drawings are odd but also strangely haunting. Whether a Mums, Chrysanths or a Camellia, she isolates her subject, centring and suspending it in a void. Her approach to composition is weirdly modern through its radical decontextualization. Did you know she died a year before you finished your rose drawing?

Despite the time between us, we have something in common: the Fuchsia Beacon in your drawing. Two years ago, I planted a few of them directly in front of my garden house in the area where concrete slabs were once buried. They are next to the golden Kerria japonica ‘Pleniflora’. Most of my Fuchsias flourished in the first year, but only one remained due to several hard freezes last winter. As the last of its kind in my garden, I can tell you it’s preciously tended to in the hopes it will flourish.

Looking at your drawing of the Fuchsia blossoms floating and flitting across the paper, your marks seem like a testimonial. You are both witness and stenographer.