Concrete

Then one spring, I noticed some St John’s wort (Hypericum androsaemum) and a Japanese rose (Kerria japonica) poking through the ground. Although both are spreaders, I was happy to see anything grow. To create more space, I cleared some of the mulch and started adding compost around them to enrich the soil further. Then, with a clunk of my shovel, I discovered concrete slabs were buried roughly ten centimetres beneath the surface. The more I dug, the more there were. Removing the cement tiles, I found there were three layers in total.

Concrete, that versatile material which built the immense coffered dome of the Pantheon, paved numerous city streets, defined the bold lines of Brutalist architecture and was once a pathway through my garden before being hidden underground. Its ubiquity makes it practically unseen. You could say it was also my garden’s dirty little secret. Unlike the woodchip paths I’ve laid, concrete is immutable and resists decomposition. Had I not intervened, it would have remained perfectly intact, silent under the earth like a tomb.

Exhumed and exiled from my plot, the Japanese rose blooms not only once but sometimes twice a year. I’m so partial to it that I often bring a few branches home to put in the vase on my desk. Looking at the flowers, I am reminded of the Situationist graffiti: Under the pavement, the beach. But in my case: Under the pavement the, Japanese rose.

Seeds

I’ve planted so many seeds and bulbs that have never germinated. Most lie dormant underground. Chatting with a friend the other day, she said: All seeds eventually germinate; they’re just waiting for the right time and conditions. I’m reminded of the date palm seed found in the ruins of Herod the Great’s palace in Massada. It was over 2,000 years old and yet still managed to sprout. I guess it’s about that magical and elusive formula for finding the perfect place, time and conditions. It’s the gardener’s Bermuda Triangle, where we all seek equilibrium as we navigate between the pull of each pole.

Forgotten Petals Found

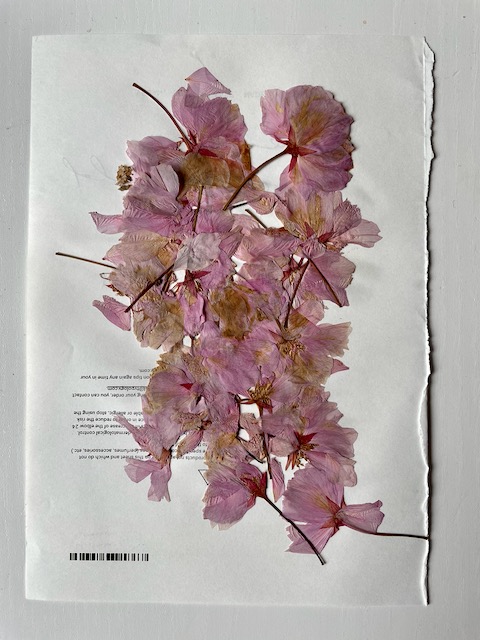

I don’t have a cherry blossom tree in my garden, but the complex paths are showered with their petals in May. It feels magical – like Dorothy and the yellow brick road, but pink. However, the technicolour is short-lived. With the first rain, they quickly turn into brown mush. I can’t remember why I saved them, but when I found them, the pink pathways of May returned.

On the back of the paper, I’ve written ‘more than human’. I was looking for an alternative way of saying ‘non-human’. It’s such an uncomfortable term that centres us as the measuring stick. The weighting of the combined words is revealing too.’ Non’, only three letters are used to describe everything in this vast world we are not. ‘Non’ for all the animals, insects, plants, and stones. It feels like an injustice.

While I don’t think he coined the phrase, I came across it when reading Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Until I find other words, it will serve as a placeholder. While more than human still holds the same measuring system, I like the hierarchical flip that ‘more than’ lends to the relation. They are, certainly by their sheer numbers alone, ‘more than’ us.

Other Plans

Do you think there is anything not attached by its unbreakable cord to everything else?

Mary Oliver, Upstream: Selected essays (p. 5). Penguin Books, 2019.

The directions on the packet were clear: spread the seeds, gently loosen the soil’s surface with a rake, and water. I did precisely that. By lunchtime, I realised my cover was blown as I watched the birds descend. Each did its round, first the blue tits, then the great tits, the dunnocks, the green finches and finally, the pudgy wood pigeons. There will be no fireworks! Not one single flower emerged, or at least not in my garden; they could have pooped them out in another spot of green. I told myself, but you fed the birds.

And don’t even get me started on the apple tree. After months of attentive work removing the codling moth’s larvae and diligently rinsing off the woolly aphids, a modest crop of apples appeared. Slowly, they’ve been plumping up and getting that hint of blush that says: I’m almost ready to eat. I can’t tell you how many nights I’ve spent mapping the tree in my mind and plotting exactly which apples to pick in the morning, only to discover the monk parrots arrived before me. Don’t get me wrong; I’m happy to share. Like me, the monk parrots are foreigners in this country. I admire the necessary resourcefulness of the outsider. What sticks in my craw is that they only eat the top edge of each apple and then move along to the next. If only they ate the whole apple, then there would be enough left to share—one for you and one for me. But again, I’m getting caught up with my own expectations. The monk parrots enjoyed the tastiest bits from the apples.

I also hung a small blue tit nesting box at the front of the house. For three years, it’s been unoccupied. The other day, I realised a woodpecker has been increasing the hole size at the front of the box. I googled this behaviour and found they usually have several holes on the go at any given time to potentially shelter over winter. Each hole is at a different stage of construction or destruction, depending on your point of view. Some may take years before they are ready to be inhabited; others are simply abandoned altogether. The woodpecker has other priorities.

The problem lies with the possessive pronoun my. If I say my friend, I don’t assume I possess that friend solely, but when I say my garden, there is a sense that it belongs to me. But my garden is actually not mine alone; it belongs to many who have other intentions and priorities.